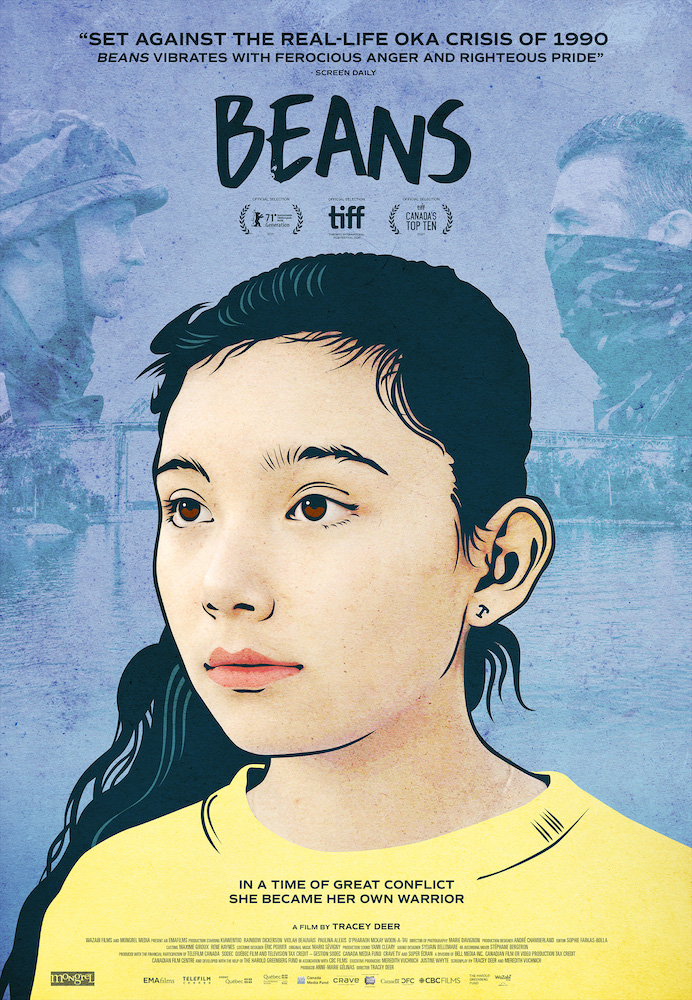

Although it happened three decades ago, the Oka Crisis remains a powerful reminder of an Indigenous struggle to protect sacred land. The 78-day standoff between the Kanien’keha:ka (Mohawks) of Kanesatake against the Surêté du Québec and Canadian military is the subject of Beans, a compelling new film by director Tracey Deer.

Since its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival last September, the film won critical acclaim and earned awards at various Canadian festivals. Its wider release was recently pushed back to July 2.

Director Tracey Deer approaches the conflict as a coming-of-age story filtered through the eyes of her 12-year-old protagonist Tekehentahkhwa, who everyone calls Beans.

It was a natural choice for Deer because she was essentially that girl, living through harrowing moments, including driving with her family through a barrage of rocks as they fled their home in Kahnawake in a convoy. Wanting to share the destructive impact of that summer sparked her desire to become a filmmaker.

“It’s a story I’ve wanted to tell since I lived it,” Deer told the Nation. “This has definitely been 30 years in the making. I wanted Canadians to experience that summer from our point of view in order to build bridges, compassion and understanding so these kinds of things don’t happen anymore.”

Months of peaceful protest against the expansion of a golf course onto a Mohawk burial ground and forest known as the Pines escalated July 11, 1990, when Quebec sent in an armed tactical unit and a police officer was killed. As the Mercier Bridge to Montreal’s south shore and other roads were blocked, tensions rose higher after thousands of Canadian soldiers were deployed.

“That summer is when my innocence was shattered and I became aware of what it means to be an Indigenous person in this country,” explained Deer. “I suffered self-worth issues, a sense of feeling unsafe in the world, and I don’t think any kid should experience that. This story is about that kind of intolerance and racism, how destructive it is for our children and communities.”

The audience perceives this increasingly hostile environment through the struggles of Beans, a smart and cheerful older sister navigating her own growing pains. While her parents debate the merits of sending her to a predominantly white private school, Beans becomes drawn to a group of trouble-making older kids and their darker world of violence, sex and alcohol.

Even as she enlists one girl to toughen her up and engages in unwarranted violence, Beans’ sweet nature shines through in ways both humorous and heartbreaking. Kiawentiio is magnetic in the lead role, portraying Beans’ dramatic journey from innocence to outrage with nuanced passion.

“The actors we chose are incredibly talented and went above and beyond my expectations,” Deer enthused. “The casting process was very fun. Young Indigenous kids from across the country sent in videos. We were able to mix and match the shortlist to see what the chemistry was like.”

Kiawentiio had earlier made a mark in the third season of Anne with an E, when Deer joined the television series as co-executive producer and contributed to a new Indigenous storyline. The young Mohawk actress is also an aspiring singer/songwriter and wrote a song during the making of Beans that plays over the closing credits.

While the writing process involved numerous drafts over eight years, Deer’s entire career has been leading to this debut feature. She devoured books and other media about the Oka Crisis, including Alanis Obomsawin’s series of films, which also informed some of her previous work like Mohawk Girls.

“I’ve been researching the Oka Crisis for my entire adult life as I process my own trauma and try to understand how that affected me,” explained Deer. “In the writing of it, I definitely had everything already compiled, both from my own recollection as well as all the other sources I’ve been exposed to. The historic events that are recreated in the film are very much actual events that took place.”

While some of the more traumatic recreations were shot in other locations so as not to inadvertently offend community members, the film crew were welcomed to shoot in the Pines. This land at the heart of the crisis is still under dispute, as it has been for 300 years.

The Mohawk Council of Kanesatake is currently suing the municipality of Oka over a bylaw that would designate part of the land a heritage site, which the band calls “a disguise to dispossess the Mohawks of their land governance.”

Inflammatory comments from the mayor of Oka in recent years indicate that the racial tensions depicted in Beans still exist. Besides including shocking scenes of Mohawk families being denied groceries as onlookers taunt them with slurs, the film interestingly intersperses actual news footage from the era with angry white Canadians advocating violence.

“It was really important to me to have the archival footage in the film because I wanted to make sure audiences understood this really did happen,” asserted Deer. “When we’re uncomfortable by what we see, a natural defence mechanism is to say that it didn’t really happen. I wanted viewers to sit with those uncomfortable feelings because that can lead to action and change.”

When nationwide protests in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs in British Columbia erupted last year, the Oka Crisis was often evoked as a reminder to avoid escalating the conflict. While many say the 1990 standoff sparked a change in how police use force and led to a greater awareness of Indigenous issues, others question whether Canada really learned anything.

For Deer, the Oka Crisis represents the type of racism Indigenous people experience every day. The emotional film production was a way of telling her 12-year-old self that she matters and this important time in her community’s history will not be forgotten.

“Even though this is a period film, the themes and what goes on in the film is unfortunately very current,” Deer shared. “The footage is from 31 years ago, but these images are still played out today in news coverage all the time. There has not been enough change – the lessons have not been learned from the Oka Crisis.”

Photos by Sebastien Raymond, Illustration provided by Metropole Films