Nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up tells the heartbreaking story of Colten Boushie

Winning a top prize for her film about Colten Boushie at North America’s largest documentary festival was a bittersweet experience for its director, Tasha Hubbard. Nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up tells the heartbreaking story of the young Cree man and his family’s fight for justice after he was shot dead by a white Saskatchewan farmer on August 9, 2016.

Making its world premiere April 24 as the opening film at Toronto’s Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival – a first for an Indigenous filmmaker – Nîpawistamâsowin earned a long standing ovation before eventually taking home the top Canadian feature documentary award, which comes with a $10,000 prize.

The difficult material is handled sensitively by Hubbard, who weaves her own life story and animated sequences about the region’s history of racial conflict into the Boushie family’s unfolding events. It was a natural creative decision for Hubbard, who grew up with loving non-Indigenous adoptive parents on a farm not far from Boushie’s Red Pheasant First Nation and whose Cree family is connected to the Boushies through marriage.

“When we heard about Colten’s death, my first response was grief for his family and what they were going through,” Hubbard told the Nation a few days after the Hot Docs media frenzy.

“Then my second thought was about the history of this place and how Indigenous people are viewed by white people. Then my third thought was what is this going to mean for children who are growing up on their own land and viewed automatically as threats, as something to be feared. That’s where it became very personal for me.”

The film begins with Hubbard’s son and nephew exploring Saskatchewan’s beautiful rolling countryside as Boushie would have, providing a gentle reminder that real children’s futures are being affected by this embedded racism.

“Indigenous people have felt that for a long time because we get dehumanized in people’s minds, in the system’s actions, in the popular media,” Hubbard explained. “It’s easier to not have to think about Indigenous people’s misery being the basis of your prosperity. That’s always been there but now in some of the ugliest social media stuff we’re actually seeing people getting pleasure from people’s pain.”

Hubbard advises Indigenous people not to read hateful comments on social media. However, she said that white people, politicians and media representatives should read them to realize the harm that these attitudes propagate. She includes samples of these violently worded online posts throughout Nîpawistamâsowin, demonstrating some of what the Boushie family endured with courage and dignity.

“This is a family that has had all this stuff piled on them: losing their son, not getting justice and then also getting hate mail,” commented Hubbard. “The mother still has love in her heart. That’s something to be learned. We’ve had all this ugliness come towards us – we’ve got to remember to love and take care of each other.”

In the documentary, viewers gain a new perspective about who Colten Boushie was and what really transpired that fateful day. We learn that Colten was a kind and generous young man, an avid reader and horse lover who had been training to become a firefighter.

“He wasn’t looking for trouble that day,” Hubbard asserted. “There’s been this big narrative of blaming the victims and it tries to recentre what happened. You can’t equate whatever was happening that day with the taking of a life.”

Filming began on the day of killer Gerald Stanley’s first court appearance, capturing the family’s anguish and community support amidst escalating racial tensions. There are frequent displays of systemic injustice, from the rejection of five potential Indigenous jury members to traumatized witnesses treated like criminals and the novel “magic gun” theory that resulted in Stanley’s eventual acquittal.

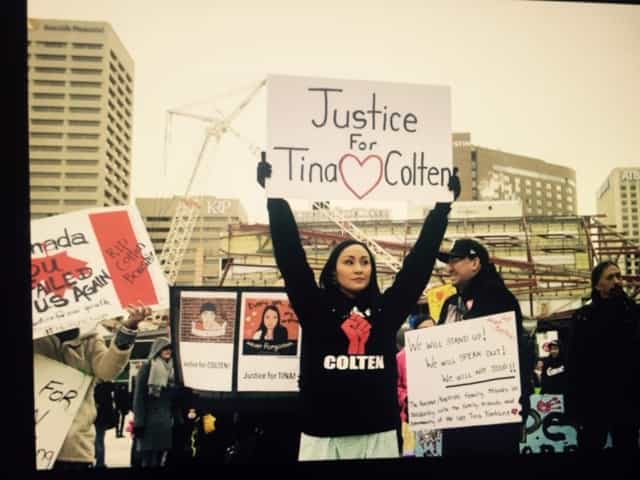

The Boushies’ quest for justice didn’t end there. As protests erupted nationwide following the verdict, the family headed to Ottawa for high-level meetings with federal ministers, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. While there was general consensus that Canada’s judicial system is problematic, the only resulting change was to the jury selection process that allowed lawyers to reject people without cause.

“I think most people anticipated at least a manslaughter conviction, so the story I had in my head was based around that,” Hubbard reflected. “I didn’t know how the family was going to get treated. They can try these things but if the system is geared against you it’s not going to matter what you do.”

Long before the Boushies reached New York City to appeal to the United Nations, Colten’s cousin Jade Tootoosis had emerged as the family’s eloquent spokesperson. Her dedication and poise are a revelation as we see her deliver a passionate speech asking for an investigation into racism and systemic bias in Canada’s justice system.

The family is still seeking a royal commission to address structural racism as well as more support for Indigenous victims of violence navigating the legal system. Hubbard hopes her film – whose title means “standing up on behalf of others” – helps their struggle and serves as a wake-up call.

“We just want people to remember Colten and to question deeply rooted beliefs about Indigenous people that are very harmful so we can have a better collective future,” said Hubbard. “See this young Indigenous person’s life as having value; that’s a starting point for the police, prosecutors – everybody in that system.”

“We need more love in this world and we need more love for each other.”

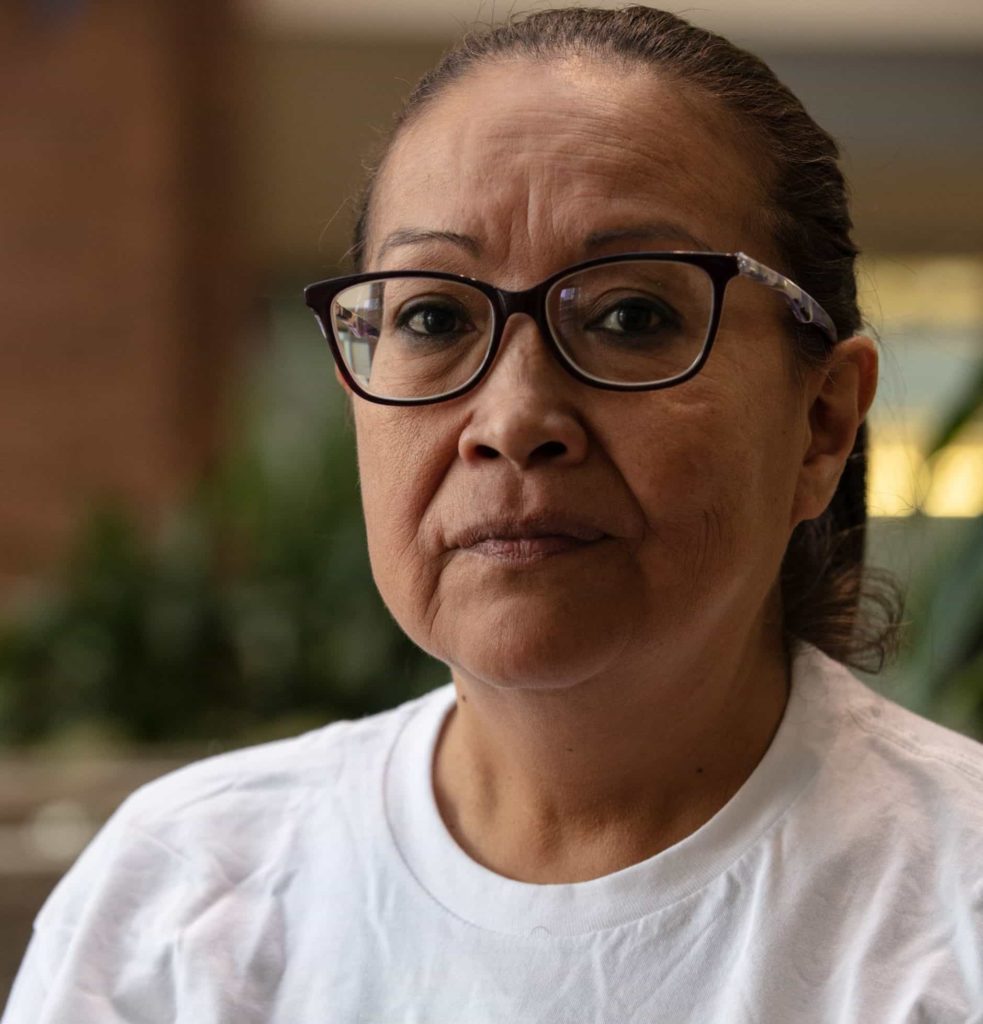

Tasha Hubbard, Filmmaker

Hubbard remembers her son and nephew playing with some white boys the day after Colten died, who she later learned were full of genuine curiosity about what it meant to be Indigenous. Then the white boys’ mother realized whom they were playing with and pulled them away. It is this deeply rooted racism that Hubbard confronts when she teaches her boys Indigenous culture and history in the film.

Nîpawistamâsowin is a must-see film, not only for the empowering resistance demonstrated by the Boushies and their supporters in the face of such senseless violence and systemic injustice – but also the tenderness at the heart of this story, the respect and generosity inherent in Cree culture that Colten Boushie embodied.

“One of the things that Colten’s mother tells people is to hug the children in your life and love them,” Hubbard shared. “We need more love in this world and we need more love for each other.”