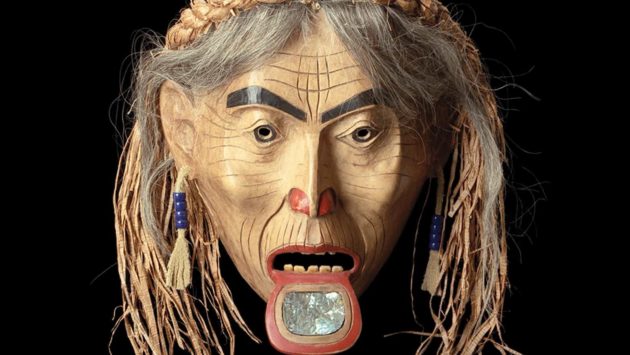

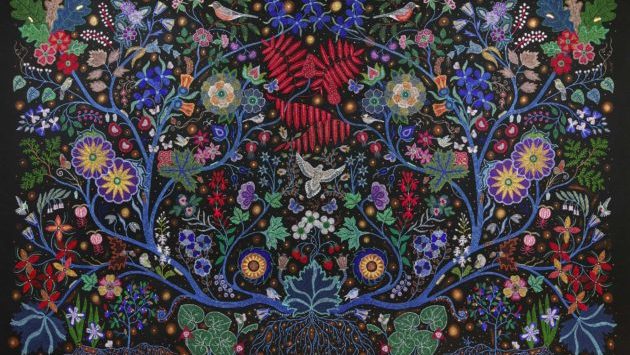

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists is a collection of 117 works by women from more than 50 communities and cultures from all over North America

In a historic first, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) has curated a large collection of artworks made exclusively by Native women artists.

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists is a collection of 117 works by women from more than 50 communities and cultures from all over North America.

The objects collected span more than 1000 years, and are made in a variety of media, including sculpture, video and digital arts, photography, textiles, decorative arts, and even a vintage El Camino. The artwork on display comes in part from the museum’s permanent collection, and is supplemented by loans from more than 30 institutions and private collections.

MIA Associate Curator Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Kiowa beadwork artist Teri Greeves are the co-curators of the show.

“The work we steward, more than 90% is historic work,” Yohe told the Nation. “I would see baskets and textiles and beadwork and ceramics, and it just kept on reiterating to me that ‘Wow, this is all women’s work’.

“I combed through the scholarship and I combed through exhibitions, and there was nothing. There were all these comprehensive shows of Native art in America, and it was never articulated that this was the work of women.”

The absence of recognition led Yohe and Greeves to begin discussing the possibility of developing an exhibition specifically exploring the artistic achievements of Native women.

By 2015, they had formed the Native Exhibition Advisory Board – a panel of 21 Native artists and Native and non-Native scholars from across North America – to provide insights from a wide range of nations at every step in the curatorial process.

They say that learning from diverse opinions and voices was a fundamental part of their approach to presenting the artwork in a way that honours both the objects and the artists who created them.

“I am aware that I have no right to talk about other tribes’ things,” Greeves wrote in an article on the MIA website. “I barely have any right to speak of Kiowa things, as I am not an Elder. And I know that the white-man world does not see things the way Native people do, so it was very important to me that we assemble as many women advisors from around North America as we could.”

The advisory board of 21 women was consulted throughout the process of narrowing down the selection of works. Once a list was drawn up, the board helped the curators understand if and where they had over-represented or under-represented some works, peoples, time periods and mediums.

The advisors were also invited to write essays in the catalogue for the exhibit, and to speak on panel discussions about the exhibition, so that multiple Native voices could be heard from different Native perspectives.

“We really made a concerted effort to work with the idea of consensus,” Yohe added, “and to be as comprehensive as we could. That consensus-building, and that community-oriented approach is a model that leads to much richer, much deeper understanding.”

With that in mind, the curators chose to avoid the typical model of organizing a show of Native art by chronology or geography. Instead, they chose to organize the exhibit thematically, by asking themselves the question, “Why do Native women make art?”

The resulting answers led them to divide the exhibition into three sections: Legacy, Relationships and Power. In an attempt to avoid the generalizing practices common to past museum shows of Native art, each section brings special attention to the individual women who created the objects on display.

“Native women have remained anonymous in so many cases,” Yohe said. “But they’re not anonymous in their communities, and they haven’t been for millennia. “These women were not only master artists, but were formidable in their communities. They were diplomats, incredible entrepreneurs, leaders in their community.”

…

Hearts of Our People is presented by the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, and runs at MIA (June 2-Aug. 18). The exhibit then travels to the Frist Museum in Nashville (Sept. 27, 2019-Jan. 12, 2020); the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (Feb. 21-May 17, 2020); and the Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa (June 28-Sept. 20, 2020)