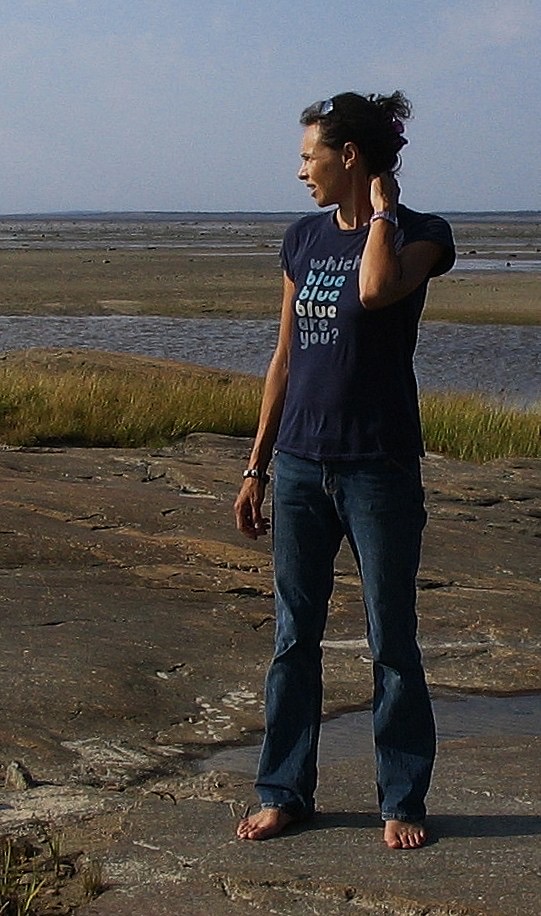

For Margaret Orr, being on the land is everything.

“I grew up the traditional way of knowing from my mother and my relatives in Chisasibi,” Orr recalled. “Back then, it was Fort George. I learned how to hunt and to fish, how to live on the land and build shelters.”

The land also made Orr the artist she is today, with her work based on the land, the water, sky, people and animals.

After completing her Master of Fine Arts (MFA) at the University of Regina last December, Orr returned back to the land in Eeyou Istchee, and now lives and works in Ouje-Bougoumou.

But it has been a long path for the multi-disciplinary artist, whose journey has come full circle.

At 28, Orr left Chisasibi with her children to study Fine Arts at Heritage College in Gatineau. “I left my community as a single mother with three children. I was young, had a lot of energy and embraced whatever came my way – the good stuff and all the obstacles,” she said.

Once her program was done, she returned home. Soon after, however, her mother Gracie Snowboy Herodier, passed away. “My mother was an artist,” Orr said of the woman who was one of her biggest influences. “Sometimes I say that she ‘is’ an artist because in her art she is still alive.”

Orr said that her mother drew, did bead work and embroidery based on traditional ancestral designs. Her father, John Patrick Orr, was an actor who got her interested in film, another aspect of art that she works in “on the side.”

After her mother passed, Orr decided to further her art education and enrolled at the University of Regina.

She continued her education at the En’owkin Centre in Penticton, BC, studying Aboriginal creative writing, and Aboriginal leadership and development.

Upon returning to Quebec, Orr had a realization. “I noticed I had been teaching ever since I started school,” she said. “I was always helping the teacher and helping other students.”

That’s when she decided to pursue a teaching certificate.

So she returned to the University of Regina and worked on a teaching certificate in visual arts. She then was able to follow her passion. “I was teaching as a certified teacher but unfortunately I got ill and didn’t have the energy to teach young people anymore.”

Still wanting to teach, she went back to Regina to learn how to teach to adults in learning institutions and completed her MFA. “My focus was on the 10,000 caribou that drowned in the Caniapiscau River,” said Orr.

That event happened in 1984, when Hydro-Québec opened the Caniapiscau spill gates, which led to a fast rise of the water level. At the same time, the George River herd, which numbered in the thousands, was crossing the river more than 400 kilometres downstream near Limestone Falls. The surging water swept thousands over the falls.

Orr’s graduating exhibition, 10,000 Drowned, held in Regina last fall, was based on this disaster. It consisted of six paintings, ceramic vessels and caribou horns, along with a video, which includes a poem she wrote.

Her paintings are now part of the Kahwatsiretátie: Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie (“Honouring Kinship” in Mohawk) exhibition of the Contemporary Native Art Biennial 2020 and can be seen on the BACA website.

Orr is now working at Aanischaaukamikw, the Cree Cultural Institute, in Ouje-Bougoumou. She recently finished a series of workshops teaching traditional painted designs in Ouje-Bougoumou, Mistissini, Eastmain, Chisasibi and Whapmagoostui.

“When I was teaching the traditional designs I pointed out how it was based on the land, on the cosmos, the elements on the earth, the landscapes, the sky and the stars and what’s going on within us and how we are connected to them,” she explained.

Understanding these concepts comes naturally to most Indigenous people she added. “It’s our self-identity as First Nations people, that’s who we are.”

In her workshops, Orr had participants use waterproof ink instead of the paints based on natural materials. That’s another project she is working on.

“I’m researching the painted caribou skin coats and the paint that they used a long time ago,” Orr said, adding that she hopes to find a way to make a traditional caribou coat using the original pigmentation recipe.

Orr says her journey through art and education has been a challenge at times. Being away from the land often made her homesick.

“I looked at it as I was going on a venture. Cree people were a nomadic people – we weren’t tied down to one place. We went where we had to get the things that we needed to survive. So, getting an education is a way of survival,” she said.