The Hudson Bay Summit brought together community representatives, Indigenous organizations and other partners in Montreal November 29 to December 1 to build on the success of the inaugural summit in 2018. With workshops focused on coordinating solutions beyond jurisdictions, an expanded Cree presence highlighted emerging issues around James Bay.

“It’s the waters that connect us and the boundaries we create that separate us,” said Deputy Grand Chief Norman Wapachee. “It was all about working together towards a common vision to safeguard the bays, people and ecosystem. It’s important for us Indigenous people to be part of whatever is being planned.”

With Grand Chief Mandy Gull-Masty occupied at Quebec’s National Assembly, Wapachee presented developments regarding the Eeyou Marine Region (EMR) and the growing role Indigenous communities are playing in global conservation efforts. Wapachee established upcoming meetings with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and detailed the progress toward a new Cree Nation research institute.

“Studies can better understand the long-term impact of development,” explained Wapachee. “Before you had people studying the Cree like through a microscope. It’s time for the Cree to flip the microscope and look out to the world, how we can preserve it for future generations.”

The Hudson Bay Summit is designed to prioritize Indigenous perspectives. Putting aside political issues, participants build bridges between cultures and knowledge systems for the benefit of the bay.

The Hudson Bay Consortium evolved from Indigenous-driven efforts in the 1990s to address cumulative impacts in the region. Cree and Inuit communities jointly authored documents “Voices from the Bay” and “A Life Vest for Hudson Bay’s Drifting Stewardship”, which pooled traditional knowledge to analyze environmental change.

The first Hudson Bay Summit focused on coordinating research, planning protected areas and coastal restoration sites, resulting in many projects moving from concept to reality. This year’s attendees were determined to take emerging networking and funding opportunities to the next level.

“Each of these research projects help move the broader vision forward,” asserted Consortium chair Ryan Barry. “Now that these initiatives are becoming realized, how do we start thinking into the connectivity between each – animals and water don’t care about lines on the map. Every community has a piece of the puzzle and by working together we can build that picture.”

During the roundtable of 28 communities, participants spoke of climate change impacts, deteriorating ice conditions and new invasive species. The delegation from Churchill, Manitoba, said there were fewer seals and beluga whales but far more orcas. Some speculated that hunted seals are sinking faster than in the past due to diet-related diminished buoyancy.

Anecdotal accounts of declining caribou and increasing muskox populations demanded further research. Polar bear counts were down in some areas but up in others. Birth defects, unknown sicknesses and taste differences were observed in certain wildlife. Both sides of James Bay noticed shrinking goose numbers in summer.

“In the 1990s, geese would be nesting on the islands, feeding on eelgrass,” said George Natawapineskum from Wemindji EMR. “Now they’ve gone further north, I guess. I’ve noticed even the berries they eat in the summertime aren’t there anymore. What I saw from the Inuit here, they’ve got more berries up north – geese go where they can feed.”

Many blame hydroelectric dams for the influx of freshwater affecting James Bay’s vegetation but Natawapineskum suggested melting ice from climate change may also be a factor. He has found the summit very productive, with valuable input from the DFO and Inuit delegates regarding the prospect of commercial fisheries in Wemindji.

Delegates heard presentations on an initiative to reinstate traditional place names and a new app called Siku, by and for Inuit. With ice safety an increasing concern, the mobile tool enables members to share hunting stories and traditional knowledge, along with wildlife, weather and land updates, producing data that can support community-led projects.

“We’re becoming very educated with this summit,” said Akulivik mayor Eli Angiyou. “It’s a summit that clearly defines what Inuit and Crees can do based on their own research. There’s funding readily available. All you have to do is get up and do something about it.”

The immense territory and complex jurisdictional overlap have long made Hudson and James bays one of the least-studied and funded regions of the country. Initiatives like last summer’s Pristine Seas expedition are starting to change that. Oceans North’s Jennie Knopp shared a teaser clip at the summit about the expedition’s work exploring the region’s biodiversity to support Indigenous-led marine conservation.

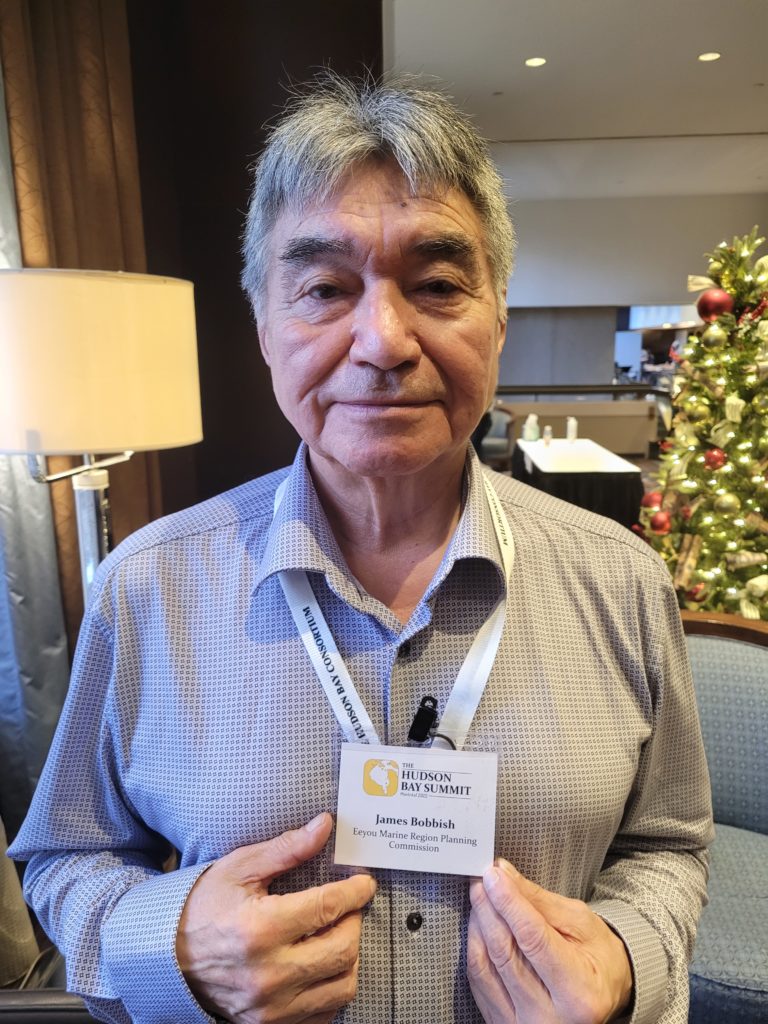

Many of Eeyou Istchee’s environmental leaders participated in workshops about protected areas and community monitoring. New chair of the EMR Planning Commission, James Bobbish, is gathering information about a proposed National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA). He told the Nation there were still overlap issues on offshore islands to be resolved with Nunavik.

In the week following the summit, the federal government announced $800 million to support four Indigenous-led conservation projects, including the NMCA within Mushkegowuk territory on western James Bay and southwestern Hudson Bay. The agreement will help conserve the boreal forests and ancient peatlands covering almost a third of Ontario that store billions of tonnes of carbon.

“Some were saying the protected area started because of the 2018 summit, getting the right people in the room who were willing to help us and support our vision for protecting our land our way,” Barry said.

With the establishment of a new Arctic region in 2018, the DFO’s Gabriel Nirlungayuk and the Canadian Coast Guard’s Neil O’Rourke presented opportunities for project funding and development. They shared that their new approach, inclusive of all Inuit Nunangat regions, reflected what was heard at the 2018 Hudson Bay Summit.

As feedback from this summit is distilled into a new five-year strategic plan and a public report to be released in the coming months, the Consortium hopes to build momentum for more of these developments that colour outside the map’s lines.

“Indigenous communities now have direct access to research funding,” said Wapachee. “There will be many opportunities for us to engage in meaningful research to better address issues we encounter in our daily life here on the land and out in the bays.”